Mexico Between Drones and Extraditions: Strategic Cooperation or Hidden Submission?

Two massive extradition rounds that, in just six months, emptied Mexican prisons of legendary kingpins and key fentanyl operators.

August 20, 2025

By Ghaleb Krame

Introduction

A U.S. drone hovering for hours over the State of Mexico.

Two massive extradition rounds that, in just six months, emptied Mexican prisons of legendary kingpins and key fentanyl operators.

President Claudia Sheinbaum insists there are no secret deals with the DEA. But the facts tell another story. Is this an exercise in bilateral cooperation that protects both countries, or a gradual surrender of Mexico’s sovereignty?

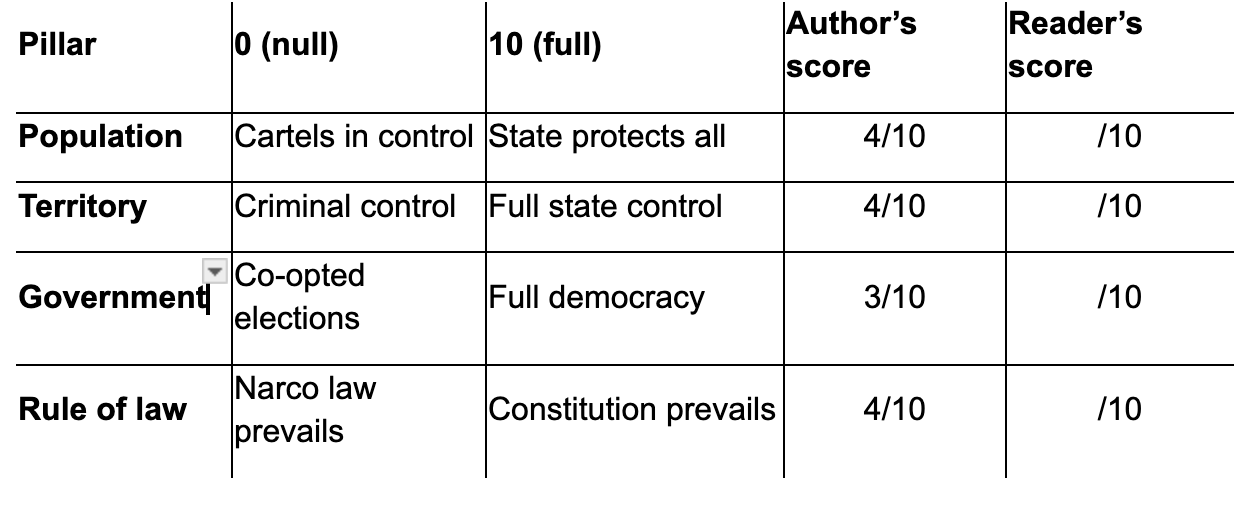

This Krame Report applies a “sovereignty stress test” across four pillars—population, territory, government, and the rule of law—to examine how drones and extraditions have become the harshest laboratory of this tension.

What is Sovereignty?

Sovereignty is the principle that grants a state supreme authority over its population, territory, government, and legal order. Since the sixteenth century, thinkers have refined its scope.

Jean Bodin, in 1576, defined it as “the absolute and perpetual power of a republic.” For him, sovereignty was indivisible and admitted no limits within state borders. Thomas Hobbes, less than a century later, took the concept further in Leviathan (1651): without a sovereign capable of monopolizing violence, men would fall into permanent anarchy, condemned to lives “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Sovereignty, in Hobbes’s view, was not decorative but the only antidote to chaos.

In the twentieth century, Hans Kelsen moved the concept toward law, arguing sovereignty rests on the Constitution and the supreme normative order that guarantees state unity. Later, Stephen Krasner (1999) modernized the debate by distinguishing three dimensions: legal sovereignty (recognition by other states), domestic sovereignty (actual control within territory), and interdependence sovereignty (the ability to decide without external impositions, especially in security and economic policy).

In sum, sovereignty is not an abstract attribute but a practical condition: a state must protect its population, control its territory, preserve a legitimate government, and uphold an autonomous legal order. Where any of these four pillars fractures, sovereignty ceases to be whole and becomes eroded, contested, or shared.

Sovereignty X-ray 2025

Sovereignty is lived, not proclaimed. In Mexico today, each pillar reveals fractures.

Population. The state is supposed to protect its citizens. Yet the 2024 National Victimization and Perception of Security Survey (ENVIPE) found 64% of Mexicans feel unsafe in their own communities. In Guerrero, Michoacán, or Tamaulipas, cartels collect taxes, settle disputes, fund festivals, and provide security. According to the International Crisis Group (2023), in multiple regions citizens pay “protection quotas” directly to criminal groups. The relationship with the Leviathan is intermittent, often replaced by “fragmented sovereigns.”

Territory. Carl Schmitt argued sovereignty is defined by control of space. U.S. Northern Command estimates that 35–40% of Mexican territory is under criminal influence. ACLED (2025) highlights hotspots in the Tierra Caliente, the northeast, and the northern border—corridors essential for trafficking drugs, weapons, and migrants. Ports like Manzanillo and Lázaro Cárdenas, gateways for fentanyl precursors, are not free of cartel control. The map of Mexico is politically fragmented.

Government. Max Weber defined the state as the holder of the monopoly of legitimate violence; Hobbes insisted on the sovereign as the antidote to civil war. In Mexico both notions are compromised. During the 2024 elections, Integralia recorded 550 attacks on politicians and candidates, including 34 murders. The electoral authority admitted that candidates in at least eight states were forced to withdraw due to cartel threats. The Financial Intelligence Unit investigated illicit financing in Guerrero and Michoacán campaigns. Mexican democracy operates under the shadow of organized violence.

Rule of law. For Kelsen, the Constitution was the state’s supreme norm. In Mexico, judicial autonomy is deeply compromised. Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción e Impunidad (2024) documented 25 judges and magistrates investigated for cartel links in the last decade. The release of Ovidio Guzmán in 2019 revealed direct cartel pressure on courts. In Chiapas or Michoacán, “narco law” or local assemblies often outweigh the Constitution. The result is a hybrid legal order where two systems coexist uneasily.

Sovereignty Index (0–10 per pillar)

Estimated 2025 result: about 15 out of 40 points. Mexico is not without sovereignty, but exercises it in an eroded, fragmented, and contested fashion.

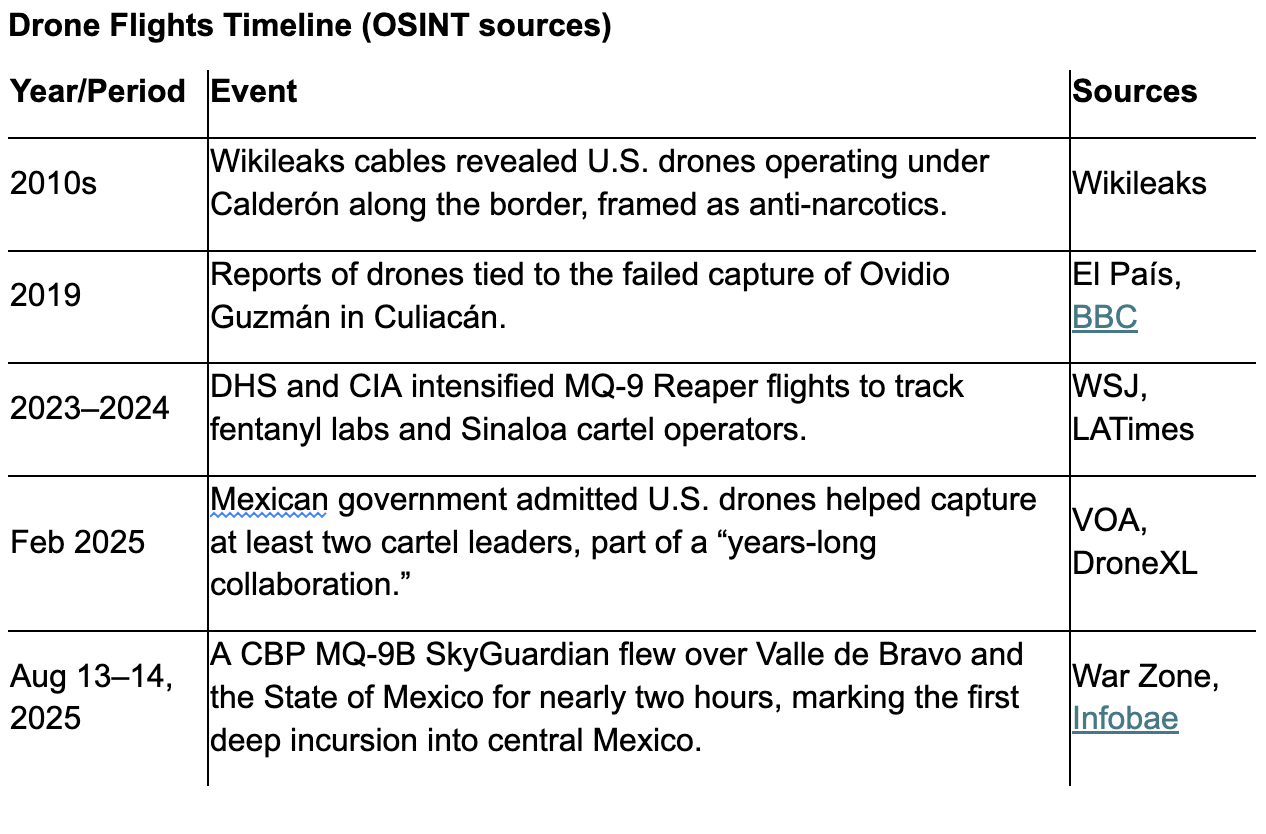

Drones in Mexican Skies: Shared Air Sovereignty

Sovereignty also extends to airspace. The Chicago Convention of 1944 established that “every state has complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory.” Yet in August 2025, it was revealed that a U.S. drone hovered for hours over the State of Mexico. Security Secretary Omar García Harfuch said the mission was “at national request,” while President Sheinbaum clarified there was “no agreement with the DEA” regarding “Operation Portero.” The contradiction between discourse and reality raises a dilemma: strategic cooperation or tacit surrender of air sovereignty?

The drone is not just a machine—it is a symbol of Mexico’s real limits. If we follow Bodin, sovereignty as absolute power, its mere presence is a cession. If we follow Krasner, sovereignty as interdependence, it could be read as strategic cooperation against transnational threats like fentanyl, weapons, or migration. In any case, the line between cooperation and subordination blurs. Mexico claims control but allows operations that, in practice, amount to shared sovereignty.

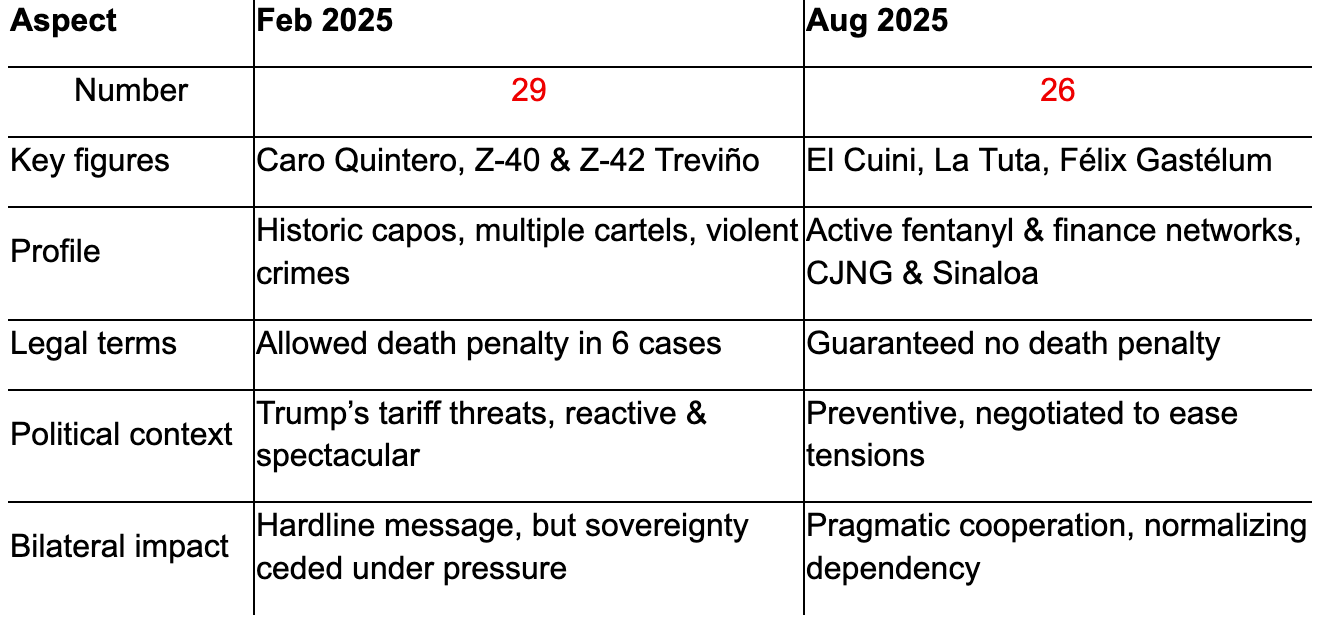

Extraditions: Binational Justice or Conditioned Judicial Sovereignty?

Extradition is one of the most sensitive tools of international cooperation. In theory, it reflects reciprocity. In practice, when most extraditions are one-way and tied to Washington’s strategic interests, the question is whether Mexico exercises judicial sovereignty or cedes it.

February 2025: 29 extradited, including Rafael Caro Quintero and Los Zetas’ Treviño brothers. For the first time, Mexico allowed six cases to face possible death penalty in the U.S.—a rupture with tradition. Context: Trump threatened 25% tariffs.

August 2025: 26 extradited, mostly active fentanyl operators: Abigael González Valencia (“El Cuini”), Servando Gómez “La Tuta,” Juan Carlos Félix Gastélum. This time, Washington guaranteed no death penalty, showing concessions to maintain cooperation. Context: Trump negotiations to avoid tariffs and military threats.

Together, 55 extraditions in six months—far beyond annual averages. For Washington, they reinforce the narrative of Mexican cartels as “terrorist organizations.” For Mexico, they project pragmatism: avoiding economic clashes at the cost of judicial autonomy.

Comparison Table:

Strategic Analysis: Useful Cooperation or Conditioned Sovereignty

Drones and extraditions are two sides of the same coin: Mexico externalizing part of its security to Washington. Both reveal asymmetry. The U.S. sets the agenda—opioids, migration, arms—and Mexico adapts.

The security results are double-edged. Short-term gains: drones locate labs with precision; extraditions surpass historic averages; DEA data shows a 12% drop in fentanyl seizures after February. But second-order effects: violence spikes (Sonora saw 18% more homicides after Caro Quintero’s extradition), cartel fragmentation accelerates, and Mexico grows technologically dependent on U.S. ISR systems.

Politically, Sheinbaum denies secret deals, but contradictions undermine credibility. Critics see submission; supporters, pragmatism to avoid economic catastrophe. Society watches a Leviathan that invokes sovereignty in words but admits foreign intervention in deeds.

Future Scenarios:

Controlled cooperation: drones and extraditions under explicit bilateral frameworks.

Gradual cession: U.S. entrenches its role, Mexico becomes a tutored state in security.

Active resistance: Mexico reclaims sovereignty, but faces sanctions, reprisals, and unilateral U.S. actions.

Conclusions

Drones in Mexican skies and mass extraditions are not isolated, but signals of a deeper process: sovereignty under stress.

The official discourse insists on voluntary cooperation, but facts show decisions constrained by external pressure and internal weakness. Drones reveal shared control of airspace; extraditions show justice subordinated to U.S. priorities.

The real issue is not whether Mexico cooperates or resists, but how much room it still has to decide for itself. Today that margin is shrinking.

Drones and extraditions are more than bilateral tools: they are stress tests of Mexican sovereignty—measuring how far a state can resist when it governs inwardly in fragments and outwardly under conditions. This is not an abstraction; it is the portrait of a Leviathan that no longer reigns alone over its own territory.

My thoughts are on the blowback on Americans visiting or living in Mexico. I fear that I may be a target of those not supporting this intrusion of the United States on Mexico. As these stories and coverage of them proliferate do I become an easy target for retribution? I feel I may become this target even as a supporter of the sovereignty of Mexico. We will see.